The Enduring Need to Protect Nuclear Material from Insider Threats

An old idiom claims that when ranking your worries, it is “better the devil you know than the devil you don’t.” When it comes to protecting dangerous nuclear material from insider threats, however, you might not have a choice. Even worse, sometimes the “devil you know and the devil you don’t” decide to work in concert against you.

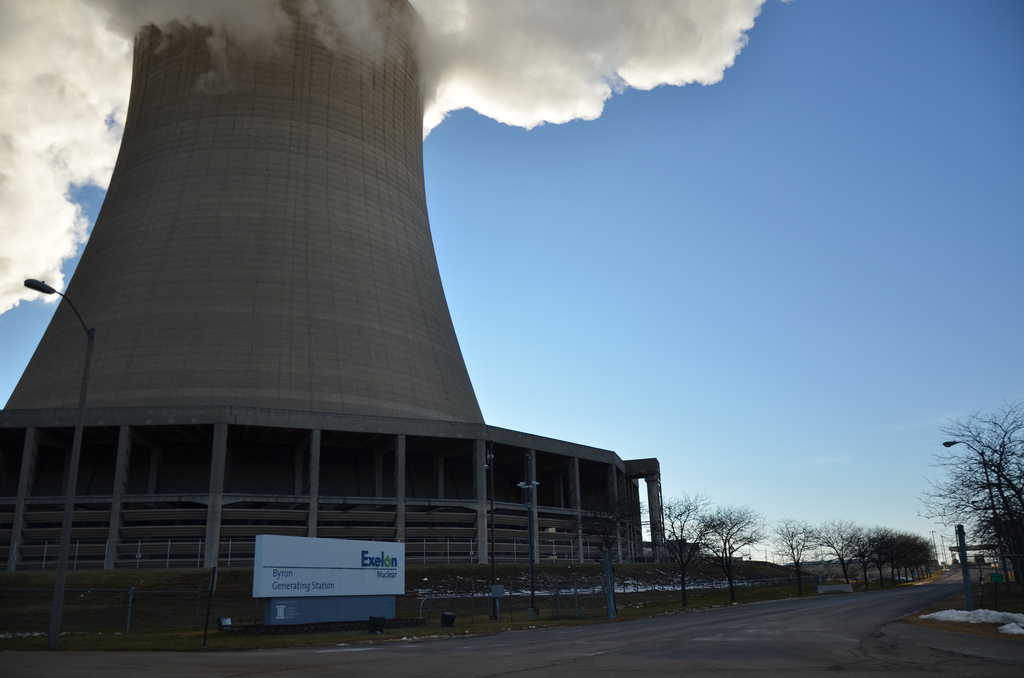

Governments and the nuclear industry put a great deal of effort into keeping the most dangerous materials out of the most dangerous hands: terrorist organizations, criminal smugglers, and other extremists. These preventative measures often involve physical security improvements at nuclear power plants, hospitals, fuel cycle facilities, and other locations with nuclear material and radioactive sources such as hiring more armed guards and installing portal monitors to detect radiation.

The job of would-be nuclear saboteurs, thieves, and terrorists to overcome these daunting obstacles would be made appreciably easier, however, if they teamed up with someone already working inside a secure facility or if they were an insider themselves. This danger is the subject of an excellent new book, Insider Threats, edited by Matthew Bunn and Scott D. Sagan, which builds upon their previous reflections on the threat from trusted employees with access to highly sensitive data and materials.

The consequences of failing to secure nuclear material would be dire, including the use of a radioactive dirty bomb or crude nuclear device in a major city or the shutdown of nuclear plant and the release of lethal doses of radiation. The world has (fortunately!) only a few known examples thus far of insiders attempting to disrupt, assault, or steal nuclear materials from their employers, so the authors decided to incorporate lessons learned from other industries trying to protect something they hold dear such as the pharmaceutical industry, casinos, and science laboratories with Anthrax samples.

Bunn and Sagan highlight a frighteningly high number of common mistakes or worst practices that exacerbate insider threats, but they also propose ideas that should interest those in the business of nuclear security.

Insider Threats Are Difficult to Discover and StopSince virtually all known cases of nuclear theft were “perpetrated either by insiders or with the help of insiders,” it is worth considering how difficult it is for organizations to detect and prevent insider threats. Managers often downplay the threat insiders pose to their own organizations – “this may be a problem for other managers and their employees, but not ours.”

Unfortunately, there are examples of insiders threats even in the most seemingly secure and prepared organizations:

Belgium: a disgruntled employee at the Doel nuclear power plant forced a shutdown of the reactor after intentionally draining the lubricant for its turbine that later needed over 100 million in repairs in 2014

South Africa: a worker at the Koeberg Nuclear Power Station successfully detonated four bombs at the facility in an act of resistance against apartheid in 1982

France: a particle physicist working at the European Organization for Nuclear Research offered help to an al-Qaida affiliate to carry out attacks in France in 2012

United States: a civilian anthrax researcher who suffered from severe mental health troubles likely mailed anthrax spores to Senators and the media in the 2000s

Reasons for Guarded OptimismIt turns out to be rather difficult for terrorist leaders to recruit insiders without the risk of being detected by intelligence agencies or observant employers. Insiders are a great help, but terrorists do not believe that recruiting or inserting their own into facilities is worth the risk; only 3 of 40 kinetic attacks (the preferred strategy of terrorist organizations) on nuclear facilities have involved insiders. However, this decision is only possible after years of hard work by the United States and others to make it tough to rely on insiders.

Nevertheless, insiders contacting outside groups or committing illicit acts on their own remains a worry. Law enforcement agencies have tried to counter this threat through sting operations and using imposter insiders to make terrorist recruiters leery of anyone offering their services. As far as stopping the autonomous actions of insiders, this will likely remain a problem for the foreseeable future. These individuals may become radicalized after undergoing background checks or they may be motivated by any number of hard to predict reasons such as becoming disgruntled with their employer, suffering from mental health issues, or financial troubles.

Overcoming Insider ThreatsInsider Threats has recommendations to encourage the nuclear enterprise to internalize this challenge and introduce adequate responses. Managers at nuclear facilities could benefit from hearing about similar threats facing other industries and organizations and learning what best (and worst) practices have shaped their experiences with insider threats. Red flag warnings about an insider becoming radicalized or their nefarious plans are often only noticed in hindsight as employers place too much confidence in background checks, the inherent trustworthiness of their staff, and their facility’s physical security measures.

Many of the ideas advanced in this book and by the IAEA are championed by CRDF Global as we implement critical programs to engage with countries to deepen the awareness of these dangers as well as best practices to prevent them from becoming a reality. For over a decade, CRDF Global has been countering the threat of illicit nuclear trafficking and improving nuclear security by increasing international access to resources, education, and training. We have worked across the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Central Asia, and have engaged over 1,500 experts from over 100 countries to help prevent the diversion of nuclear material and respond to threats and incidents. CRDF Global’s initiatives include trainings, workshops, and fellowship programs to reach students, scholars, policymakers, and the technical workforce. An enduring culture of nuclear security requires that citizens, governments, facility managers, and workers understand the value of nuclear security and how insider threats can emerge within any organization, even their own.

Here are just two examples of these vital programs that strengthen nuclear security around the globe but are vulnerable to budget cuts:

Global Threat Reduction Initiative: this Department of Energy program reduces the risk that terrorists or proliferating states acquire WMD material and expertise by promoting a strong nuclear security culture, human reliability programs, and insider threat mitigation efforts.

IAEA: U.S. support for the International Atomic Energy Agency enables it to help nations operate safe and secure civilian nuclear programs and assist with implementing insider threat mitigation best practices such as IAEA Nuclear Security Series No. 8.

The need to widely adopt nuclear security culture is more important now than ever as countries embark on ambitious nuclear energy programs and the use of radioactive sources becomes increasingly prevalent. Each additional nuclear facility requires new staff to operate the facility. Without a robust nuclear security culture and human reliability programs in place, new and untested managers will face further possible sources of insider threats.

Groups seeking access to nuclear materials for criminal purposes are constantly adjusting their strategies to probe for weaknesses in a facility’s physical security and its workforce. With terror organization such as ISIS cheering on individuals to take autonomous action in pursuit of violent ends, it is essential to remain vigilant and not retreat from successful programs that have made incredible progress in nuclear security across the globe.

Timothy Westmyer, Associate Project Manager, Nuclear Security, CRDF Global